Gerardo and Tommaso

by Marcantonio Lucidi

THE CAVE OF THEATRE

The cave of the Italian theatre of the last six to seven decades lies at the end of a staircase that opens behind the counter of a photography shop, in Rome, on the Appia nuova, in Largo dei Colli Albani. One steps down into Tommaso Le Pera's studio, set on the lower floor of the photography shop, and finds a treasure trove of several million shots. There are theatrical performances, actors, directors, sets, costumes, lighting, and if you pay attention, if you bend your ear, from the black and white images of the 1960s, from the colour of the following lustres, you can perceive in the distance, even in the background of Deafman glance (Lo sguardo del sordoby Bob Wilson, a few notes of the stage music. Le Pera's innumerable photos could be used to envelop the globe - and Gerardo Guerrieri would certainly be happy about that - to show extraterrestrials intent on studying us with their powerful telescopes, that humans not only know how to make wars, bombs and massacres, but also how to do something good. The theatre, meditations on theatre, photos of theatre. The photos represent a petrified present.

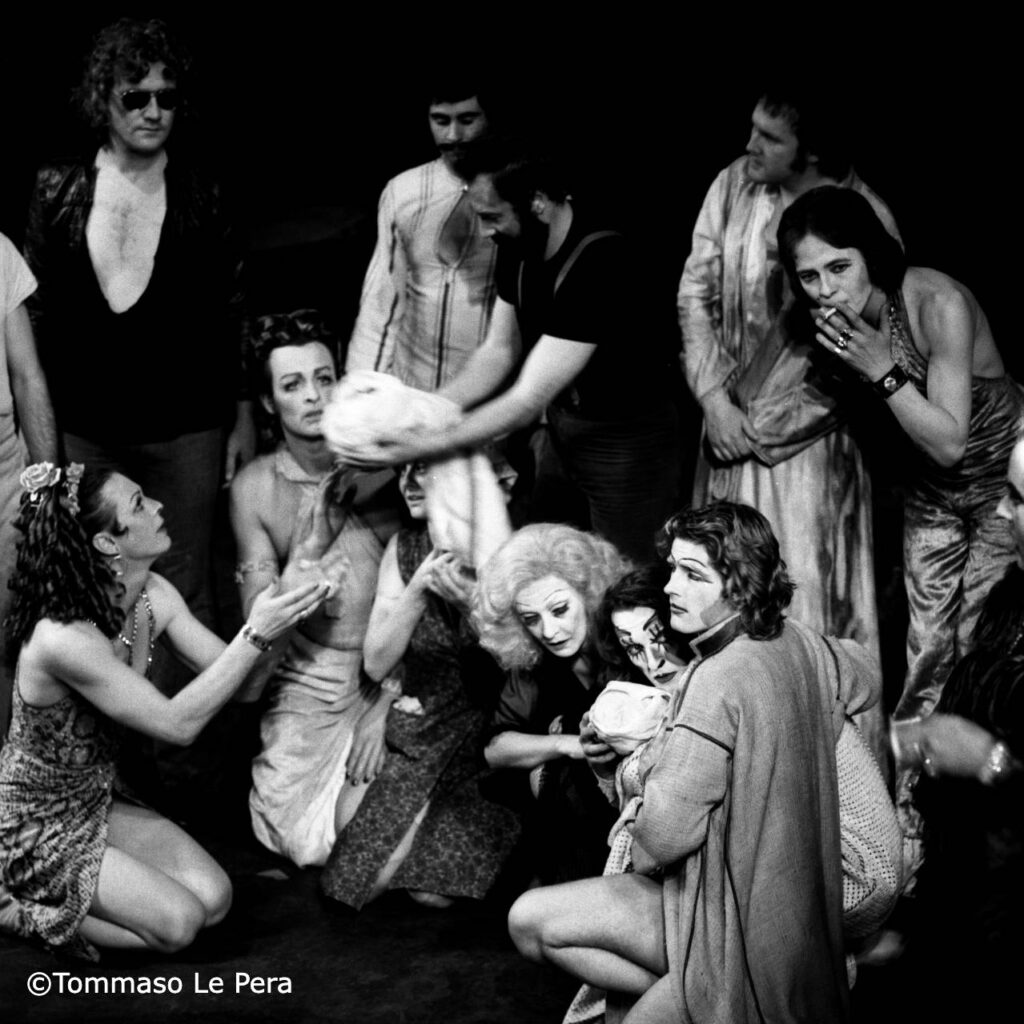

A story of Istanbul, by Erol Günyadin, Dormen Theatre company, Istanbul, Eliseo Theatre, Rome, May 3rd 1971, photograph by Tommaso Le Pera

Guerrieri, Le Pera and the novelty of Deafman glance

Inside this huge photographic cave, there is a gallery containing Le Pera's beginnings, images of the shows he photographed for the Teatro Club, the international centre of theatre culture founded by Guerrieri in 1957 together with his wife Anne d'Arbeloff with the intention of injecting cosmopolitan electricity into the Italian scene. For example Deafman glance which arrived in 1971 at the Eliseo for the Teatro Club (from that year on called Premio Roma): Wilson told the story of a teenager who had become deaf and mute as a child after catching his nanny slitting the throats of two other little ones in her care. The performance unfolded slowly over seven hours—slowness that would become a signature style—a sequence of scenes made up of unusually beautiful images, often obsessive, mental and dreamlike, which distorted the perception of theatrical space and time, opening the door to poetic expression and to an inner world in which language had lost its primacy. An extraordinary machine of freedom, as Louis Aragon called it. It was received for what it seemed to be: a revolution in theatrical representation. The world of a deaf child opened like a mouth without words, verbal language was replaced by movement. This silent work pointed the way for Italian stage artists toward image-based theatre, which became the driving force of national experimentation, particularly of the Roman school.

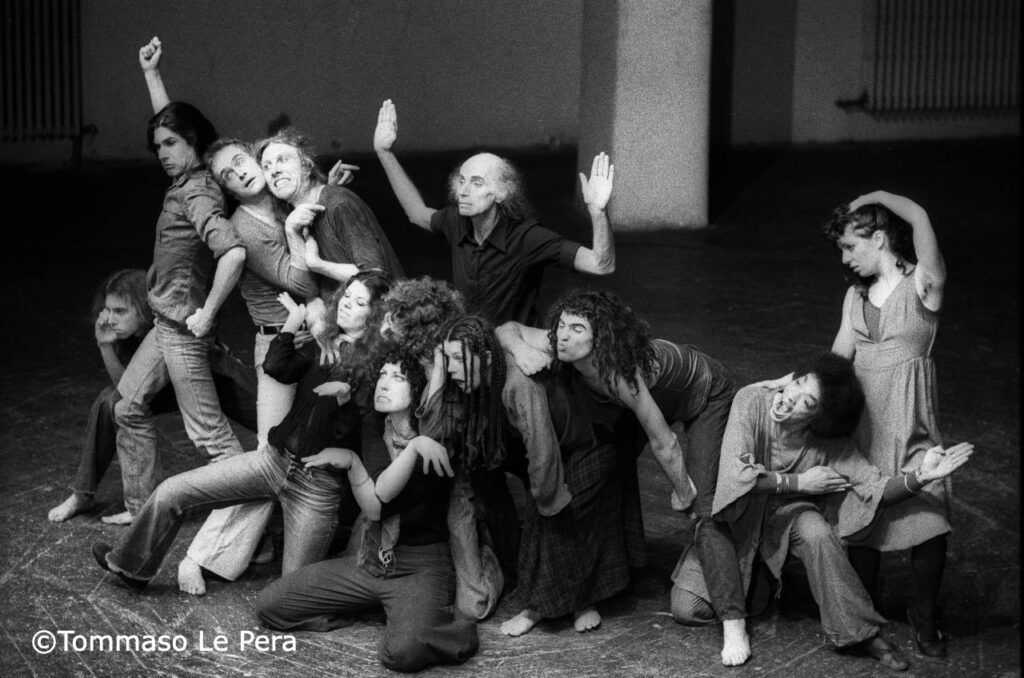

Jean-Louis Barrault with the actors of the company, in Rabelais, by Jean-Louis Barrault, Medini Circus - Gardens of Villa Medici, Rome, April 21st 1970, photograph by Tommaso Le Pera

Tommaso Le Pera found himself in those years inside the revolution of the scene, in the midst of the revolt of the image that Gerardo Guerrieri brought to Italy. While he was taking pictures, did Le Pera realise that he had captured something new? No artist knows his position in history. He does not know what he is doing, he only knows that he is doing it. Gerardo was not only an artist (director, playwright, scriptwriter, translator) but also an intellectual, theatre critic and essayist. And as a scholar he saw the position of others in history: ‘In ’71 the event is Bob Wilson's arrival from Nancy at the Rome Prize. The chronology closes with his Einstein in Venice (of ‘76). His influence is as decisive and stimulating for the 1970s as Living was in the 1960s'. (G. Guerrieri, Avant-garde and experimental theatre in Italyin The critic as spectator, Valerio Levi publisher, Rome, 1987, p. 241).

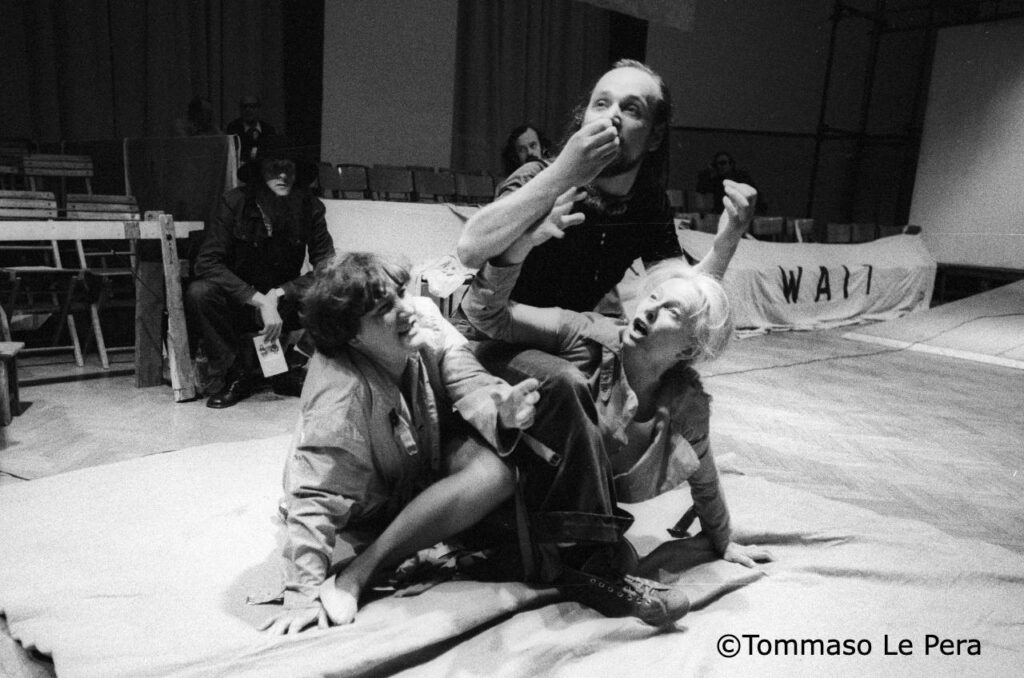

Prometheus by Julian Beck and the Living Theatre, Argentina Theatre, September 30th, 1978, photograph by Tommaso Le Pera

The boy who was a projectionist

The Living Theatre of New York arrived in Rome for the first time in 1961 thanks to the Teatro Club, which presented the group led by Judith Malina and Julian Beck at the Teatro Parioli. The connection by Jack Gelber and Many Loves by William Carlos Williams. In the cave at Largo dei Colli Albani there are no photos from those days—the young Le Pera had not yet arrived in Rome from Sersale, his hometown in the province of Catanzaro. He was gaining experience in his father and uncle’s photography shop, and from that practice he developed such skill that he became a contributor to the prestigious magazine Fotografare. His technical expertise fascinated Guerrieri, who was always eager to ask questions, study, understand: what kind of film do you use? What sensitivity? What exposure time? And the aperture?

In Sersale, the family ran a cinema, and the boy worked as the projectionist—teenagers are like that—so he fell in love with theatre, which is never just a simple love, but rather an obsession, a possession: the first trait Tommaso and Gerardo had in common. At twenty, the aspiring photographer arrived in Rome, opened his lab, and began sneaking into theatres to take pictures in secret. Theatres are vessels; the young man was a stowaway and couldn’t work with actors in pose, as was customary at the time, but could only capture them in motion—which would be an oxymoron, still in motion, like dark light or festina lente, hurry slowly. So, making a virtue of necessity, he invented dynamic stage photography, which isn’t an oxymoron, but rather a paradox. Art is always born from confronting and overcoming a difficulty—overcoming it: the hendecasyllable in poetry, motion in photography.

Le Pera used to hide at the Eliseo Theatre in the first balcony to photograph Eduardo and then very shyly bring him the prints because Luca, the son of the great capocomico, urged him: ‘Go, go show him the photos’. And Eduardo would take them. The stowaway began to make himself known to the crews of the theatre ships, the photos were beautiful, new, modern, until Gerardo and Anne gave him free access to the Teatro Club shows. He had missed Judith Malina and Julian Beck in ‘61 but now here they were in ’78 for the Prometheus at the Argentina Theatre. The image is not posed but dynamic, with Julian behind a group of actors, his bony face and hands raised with open palms in view, while Judith in front of him and among the others stands in the foreground with her left knee on the ground. A simple black and white photo, yet depicting the idea of the collective that sustained the kind of kibbutz of the scene that was Living.

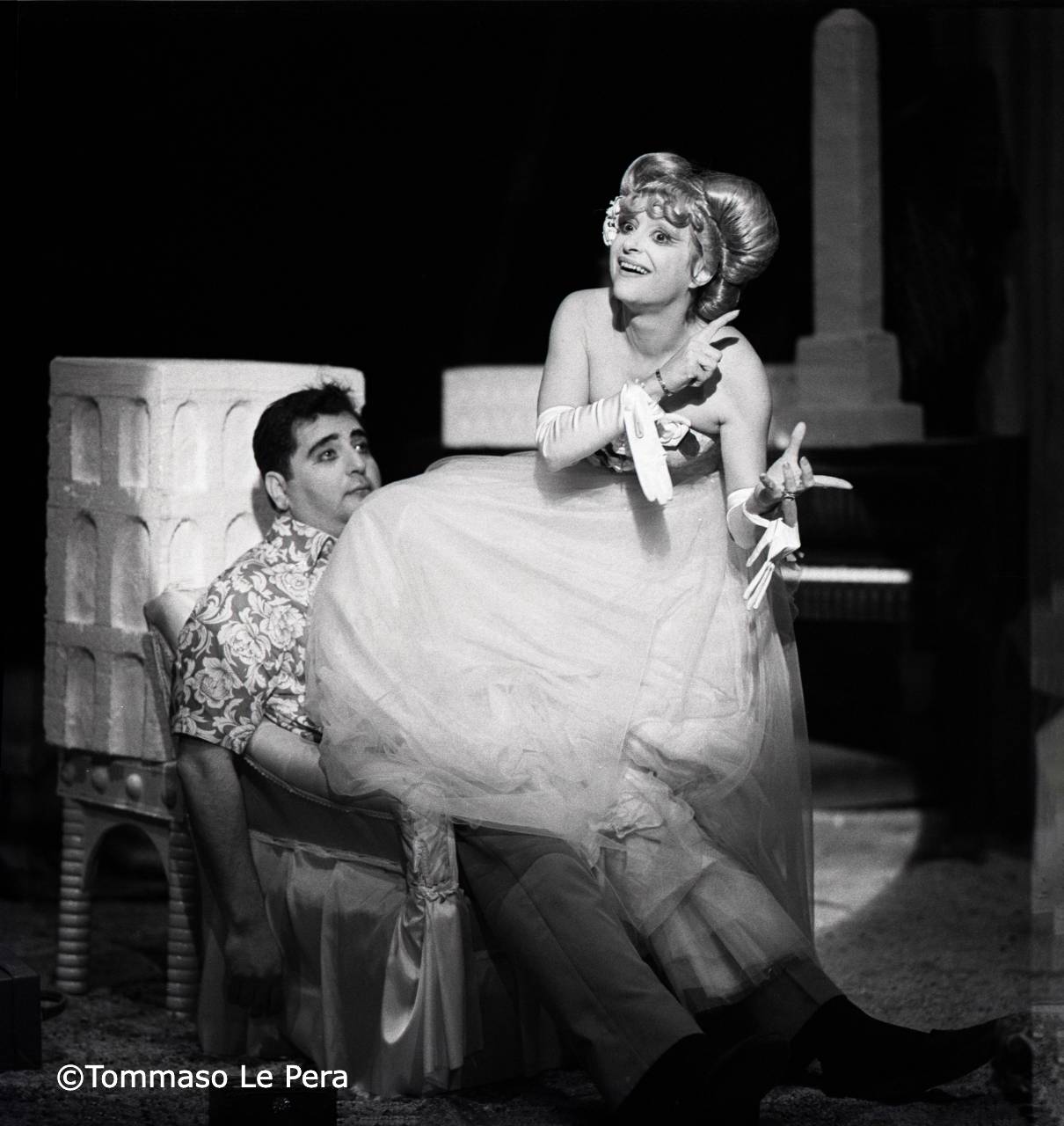

Nabodnisie i kocsodany by Stanislaw Ignacy Witkiewicz, Cricot 2 Company, Kraków, directed by Tadeusz Kantor, National Gallery of Modern Art, Rome, May 9th 1974, photograph by Tommaso Le Pera

Gerardo and Tommaso

Tommaso and Gerardo are in some ways similar, both collectors, frenzied accumulators one might say, the former a feverish preserver of scenic images, the latter of every performance created on earth. One wonders if theirs are not in fact huge piles of theatre pure and simple, theatre as such. To theatre or not to theatre, that is the dilemma. Le Pera at the table of his photographic cave brings up on the computer in one go hundreds of shots that look like rows and rows of soldiers from Emperor Qin Shi Huang's terracotta army.

For the preparation of the exhibition ‘Eleonora Duse and her Myth’ at Palazzo Venezia in 1985, the two divided the tasks, Gerardo selected the materials, Tommaso photographed them. They became friends. You can tell how much they were theatre companions by the way Le Pera looks at a digitised shot of him on the computer screen of Guerrieri sitting on a sofa chatting with Arthur Miller: ‘It was Gerardo who introduced me to Miller (pause) the show was View from the bridge (pause) at the Eliseo theatre (pause) 1984".

Gerardo Guerrieri and Arthur Miller during the press conference for View from the bridge, at the Eliseo Theatre, Rome, May 1984, photograph by Tommaso Le Pera

The magical hat of Gerardo and Anne in the photographs of Tommaso

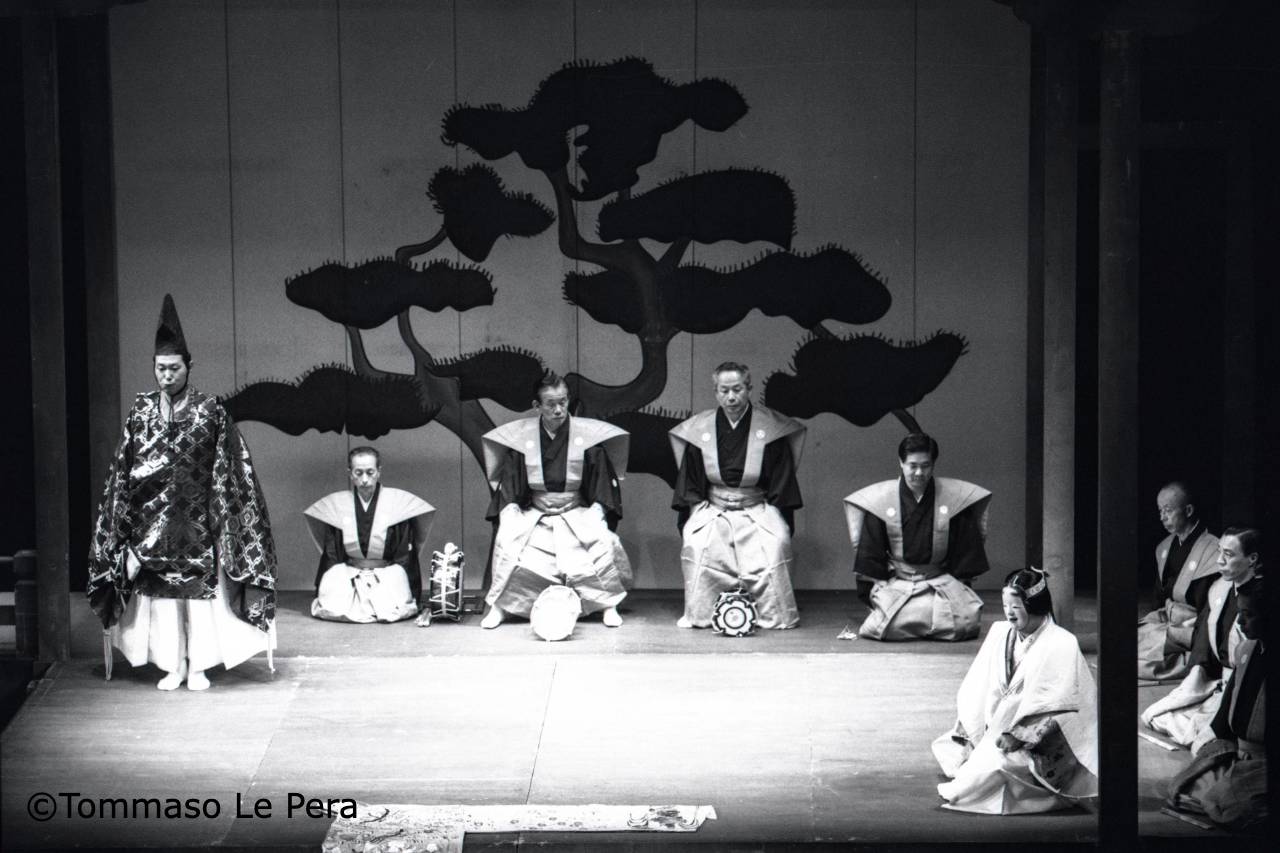

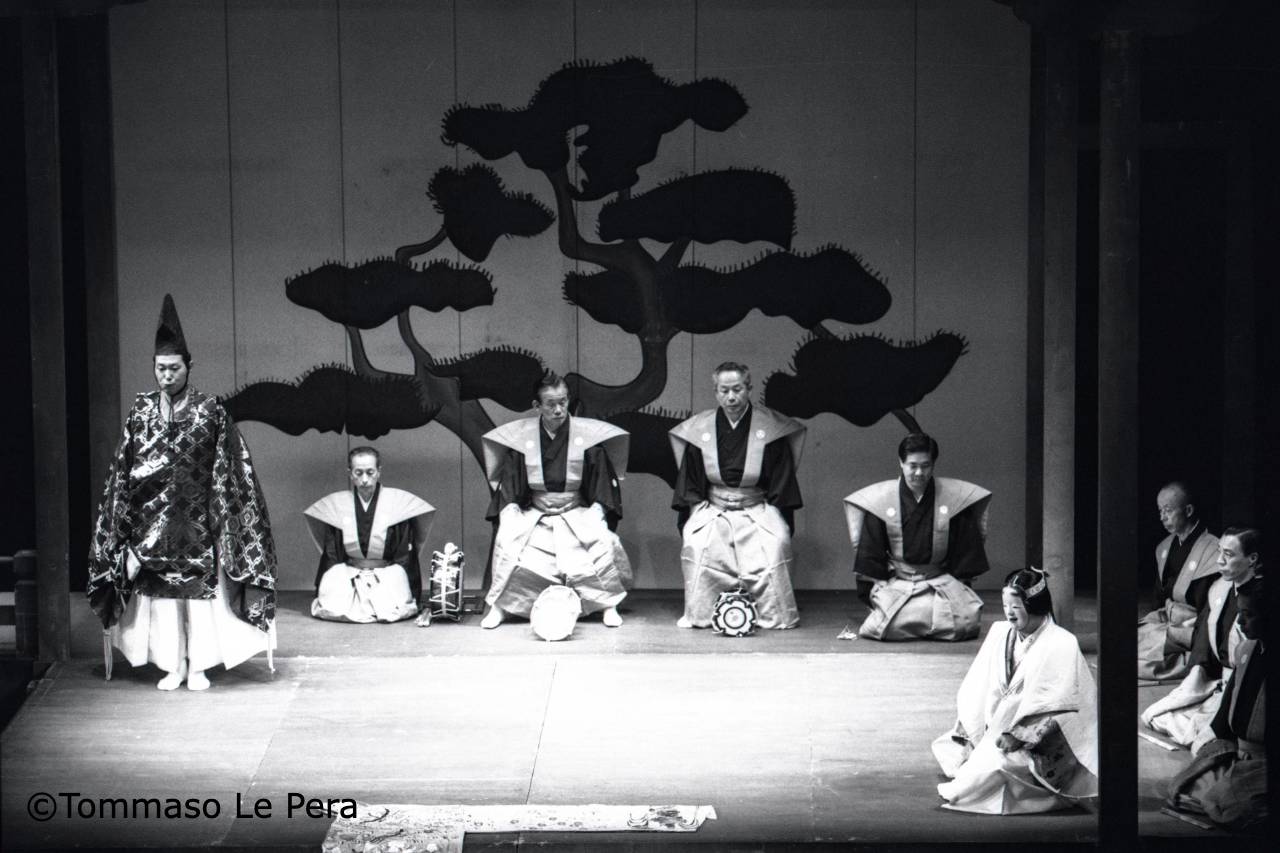

To the Italians, Guerrieri showed the Japanese of stylised nō theatre and kyōgen farce, the dancers of Bali, the Turkish actors of Haldun Dormen on stage at the Elysée in 1971 with a two-act musical play written by a famous Ottoman actor, Erol Günaydın, entitled A story of Istanbul(A story of Istanbul). There is a theatrical exoticism that makes for fabulous journeys sitting in an armchair. With music by Archie Shepp and Gilbert Moses it arrived in 1970 in a suburban Roman gymnasium called the Kilt club Slave Ship, a drama by LeRoi Jones, a black writer, polemicist and propagandist who, according to the chronicles of the time, was jailed in New Jersey for possession of arms and ammunition during the 1967 black revolt. There is a political theatre that offers intense adventures in revolution. The great critic Raul Radice wrote that Slave Ship was an ‘allegory of the navigation of a ship in the cargo of which a slaver with his face covered by a white cross gradually stuffs a number of negroes, men, women and children, poorly contained in a small space that becomes a place of torture’. A presentation page of the play written by LeRoi Jones himself read: ‘The revolutionary theatre, which is now populated with victims, will soon be populated with new kinds of heroes: not the weak Hamlets racked with doubt as to whether or not they are ready to die for their personal ideals, but men and women (and intellects) capable of digging beneath a millennium of ῾beautiful art᾿ and insubstantial amorous tinkering... We are sorcerers and murderers ... Ours is a theatre of assault. The drama that will open the sky for us will be entitled ῾The Destruction of America᾿’.

All this theatre, all this international scene revolting against the polis and power, a statutory task of the art of comedians, which came out of the magic hat of Gerardo and his wife Anne, was photographed by Tommaso. Here in one photo are also those who challenge the protesters, Jean-Louis Barrault with his Rabelais under the circus tent erected in the gardens of the Villa Medici. The great French actor had said in ‘68 to the occupants of the Théâtre de l'Odéon of which he was director together with Madeleine Renaud: “Barrault is dead, he remains a living man”. And two years later, the last sentence of the play was: ‘I walk off confidently in search of a great Perhaps. Curtain down, the farce is over'.

Books, essays, treatises, manuals, monographs and dissertations can be written about the Teatro Club / Premio Roma and Le Pera's photographs that represent the history in images of a scene that was rebellious even with the rebels, non-conformist, anti-bourgeois, unconventional, always anti because it was anticipatory. The title of this story for those who were not born or did not stay in Rome during the years of the guerrieri (warriors) couple and their great achievements between 1957 and 1978: What have you missed.

What have you missed?

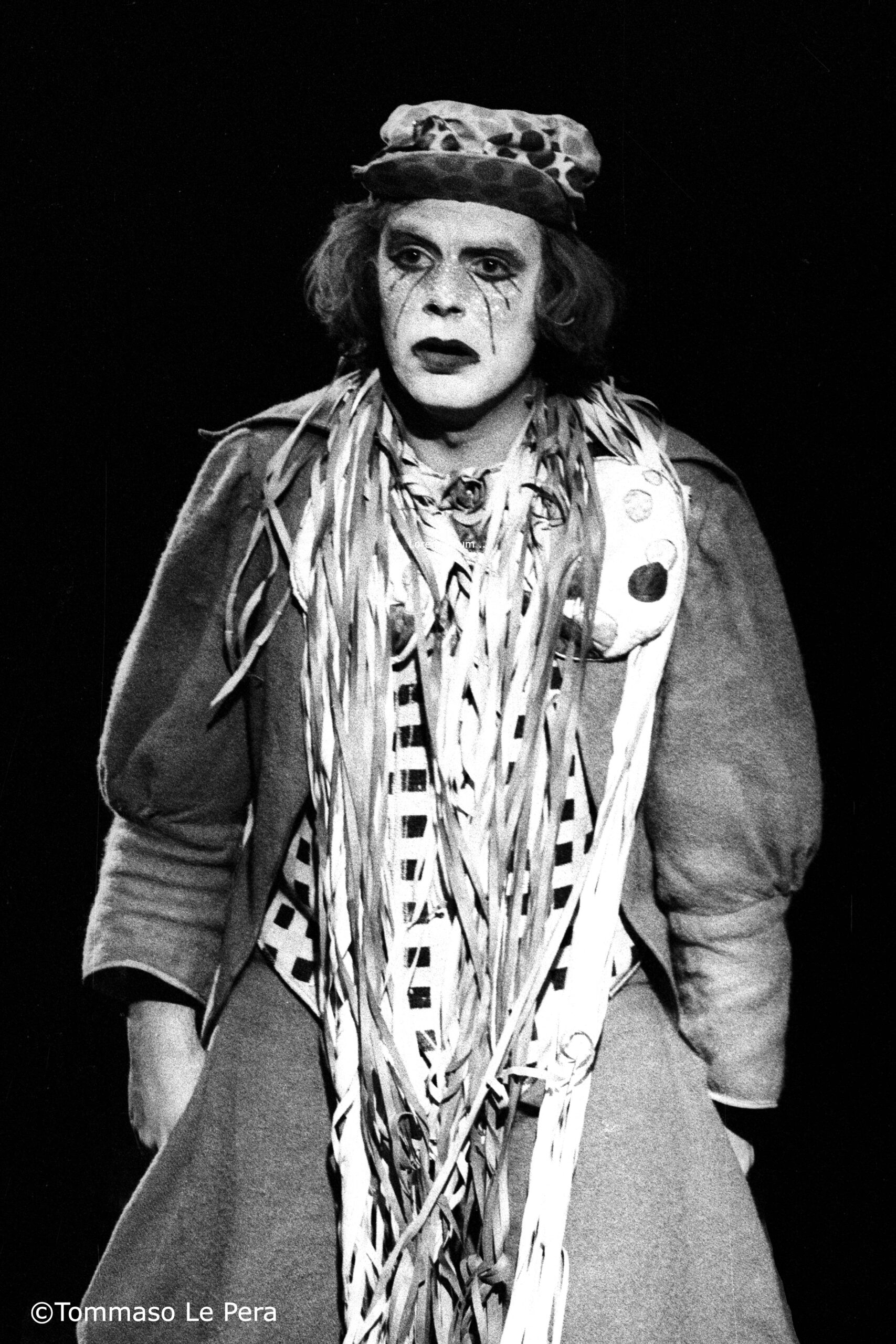

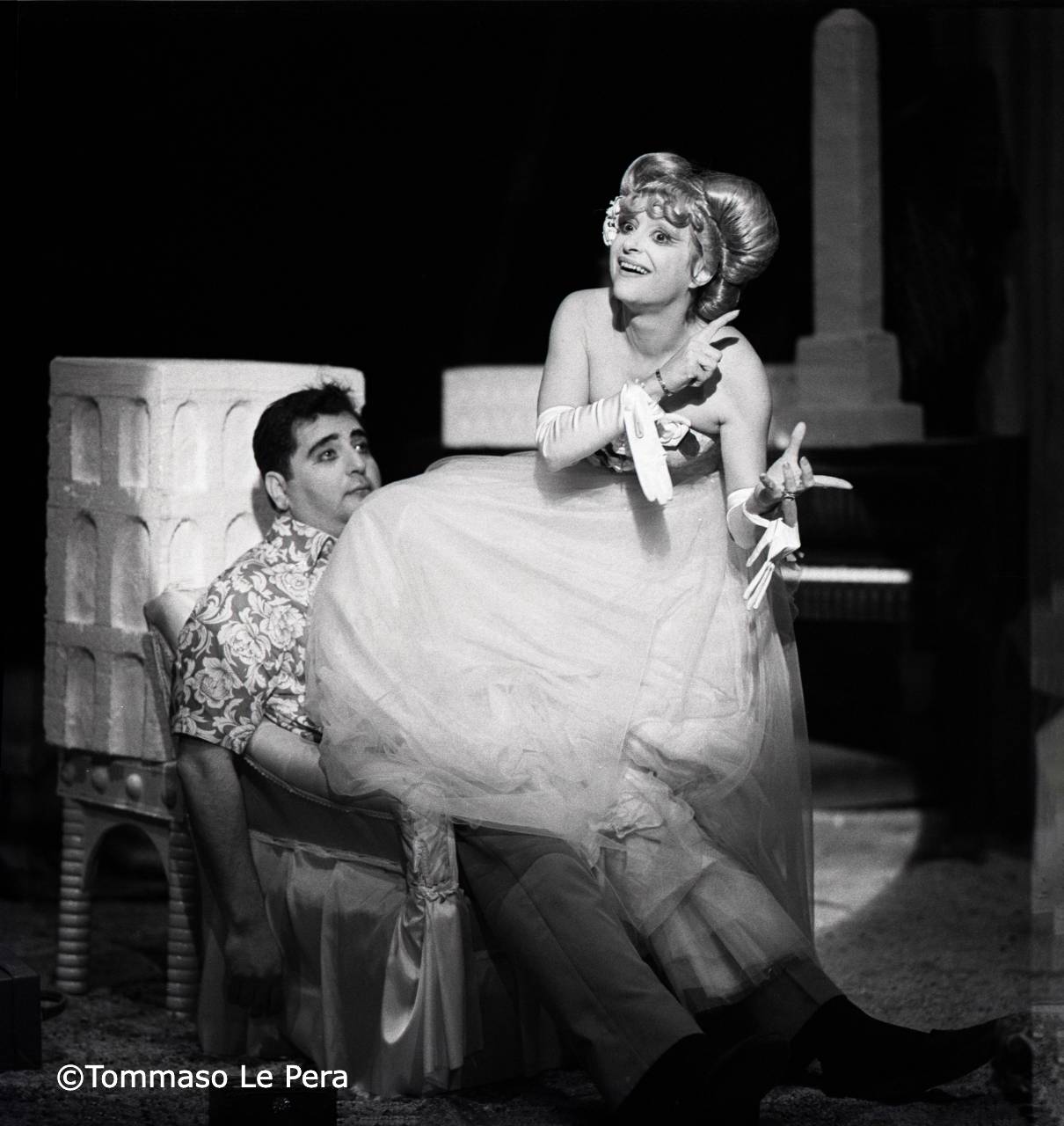

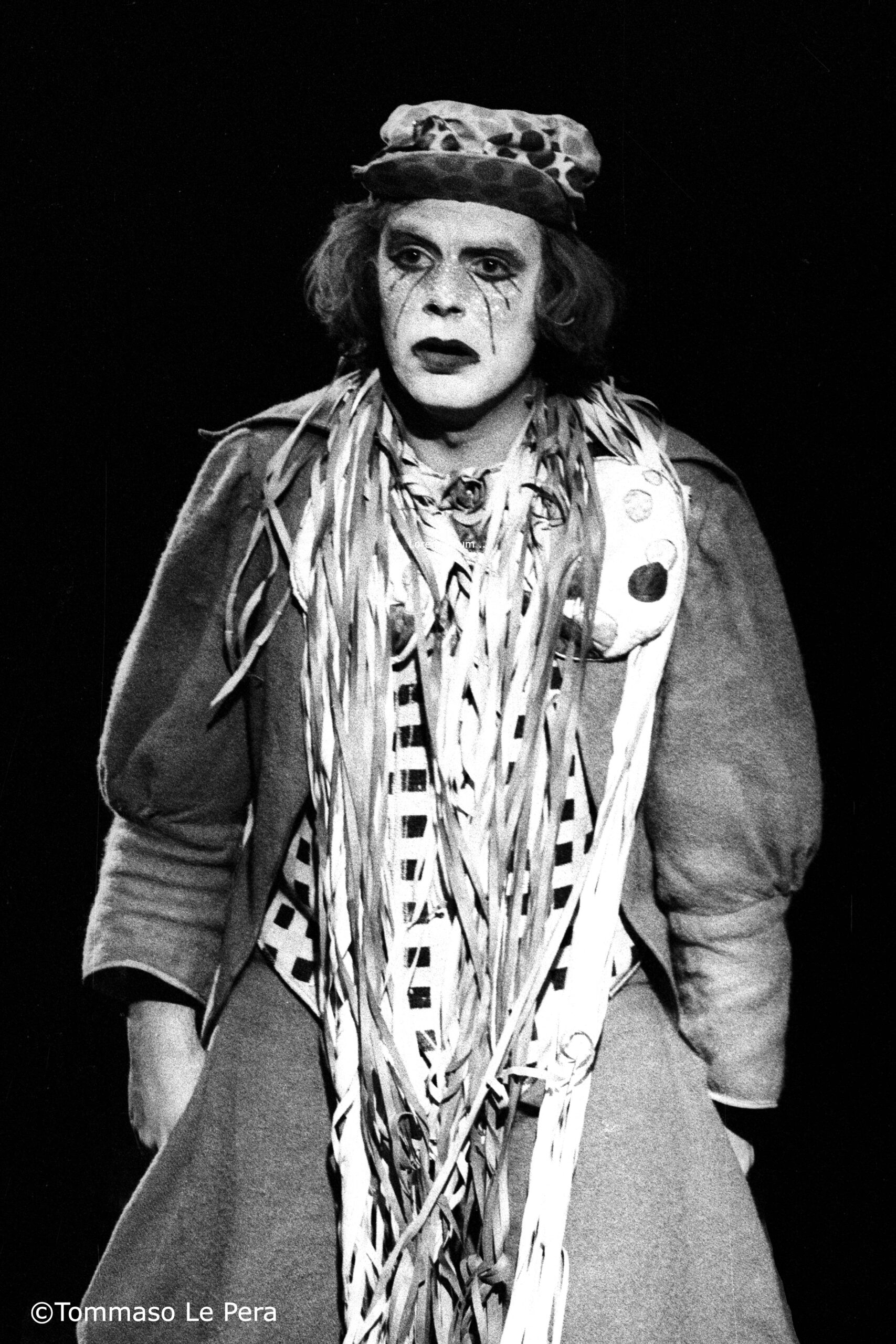

You missed the Grand Magic Circus of Jérôme Savary with The last days of loneliness of Robinson Crusoe, anche questo a Villa Medici, sottotitolo 20 years of adventures and love, texts of the songs by Roland Topor. You missed the Argentinian from Baires, of Italian origins, naturalised French Copi, who wrote Eva Peron, directed by Mario Missiroli at the Demar circus in Viale Tiziano, performed by Adriana Asti and Pina Cei. There were also Italians in the urbi et orbi theatrical universe of the artists, long before the claustrophobic global village of the merchants. Roberto Guicciardini, for example, who for Clizia by Niccolò Machiavelli directed the actors of a classic cooperative theatre company of those years, Il Gruppo della Rocca, Egisto Marcucci, Paila Pavese, Italo Dall'Orto, Marcello Bartoli who came from Milan's Piccolo Teatro, where he played Brighella and Pantalone. Even in those international Roman years, a few of the dregs of false localist intellectualism had reproached the Teatro Club / Premio Roma for being excessively devoted to outsiders. But can one seriously think that artists have a nationality, a homeland if not that of art? The performance in English The blacks, original title Les nègres, scritto dal francese Jean Genet, fu messo in scena da un greco, Minos Volanakis, che dirigeva attori provenienti da Guyana, Sierra Leone, Nigeria, Sud Africa, Honduras, Giamaica e Nord America. E chissà di che nazionalità era il Macbeth of Englishman William Shakespeare directed by the American child of Jewish Poles, Charles Marowitz? Speaking of Poles, there is a photo of the performance of a director from Wielopole, near Kraków, his name was Tadeusz Kantor, he was a giant, he came to Rome, the Rome that no longer exists, with a text by Stanislaw Witkiewicz, Nabodnisie i kocsodany. A man with two bicycle wheels, another with four legs, a third with two heads, a guy who, to the sound of a gypsy's violin, killed himself with a pistol at every turn, a woman covered only in an animal skin, others with enormous breasts made of rag bags, a man in a bowler hat who repeatedly pulled a skeleton out of a wrapper. Kantor meant that we are all poor human beings. A condition that could indeed be a flaw, but Gerardo and Tommaso managed to turn it into a virtue.